Asia’s seas offer rich pickings for marauding pirates who steal oil and supplies worth billions of dollars every year

By Adam McCauley

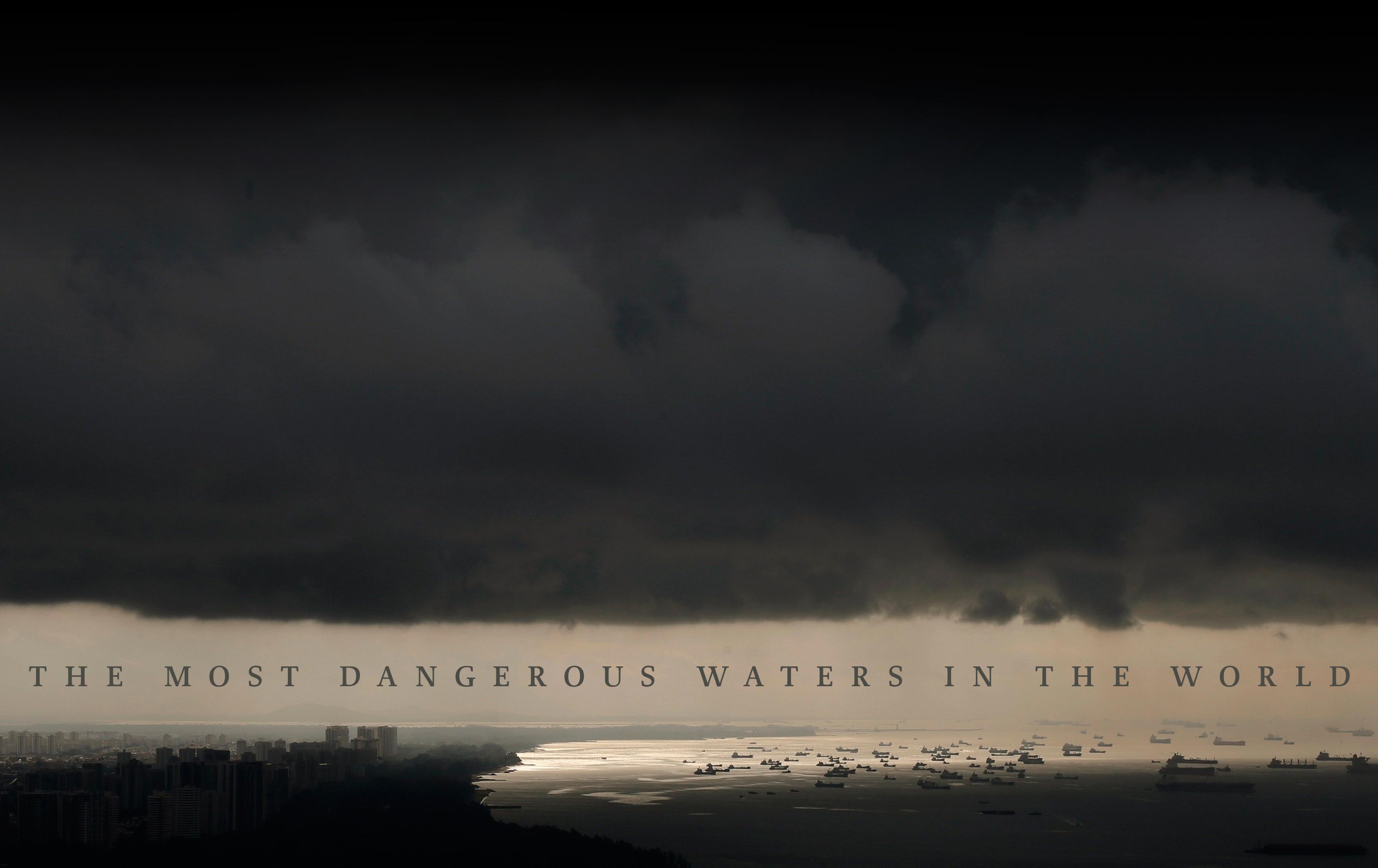

Pictured above: Vessels anchor off the east coast of Singapore on Aug. 15, 2014. Photograph by Edgar Su—Reuters

![]()

Two hours before sunset on May 28, 10 men, armed with guns and machetes, climbed from their speedboat onto the deck of a shipping tanker named Orapin 4. The ship was carrying large quantities of fuel between Singapore and Pontianak, a port on the western coast of Indonesian Borneo. Bursting onto the bridge, the attackers locked the ship’s crew below deck and disabled the communications system. They then scrubbed the first and last letter from the boat’s stern, leaving a new identifier, Rapi, in its place.

Failing to hail the crew that evening, the Thai shipping company that owns Orapin 4 reported it missing. Radio alerts were sent out, asking other vessels to keep an eye out for the ship — but nobody had seen it. Over the next 10 hours, the attackers siphoned more than 3,700 metric tons of fuel into a second vessel. Finally, four days after the attack, the Orapin 4 pulled into its home port of Sri Racha, Thailand — the town, as it happens, where the namesake hot sauce was first brewed. While the 14 members of the crew were safe, the pirates — and $1.9 million in stolen fuel — were long gone.

Under most conditions, the brazen attack on the Orapin 4 would have been notable. But this was the sixth such attack in three months.

Shipping Superhighways

![]()

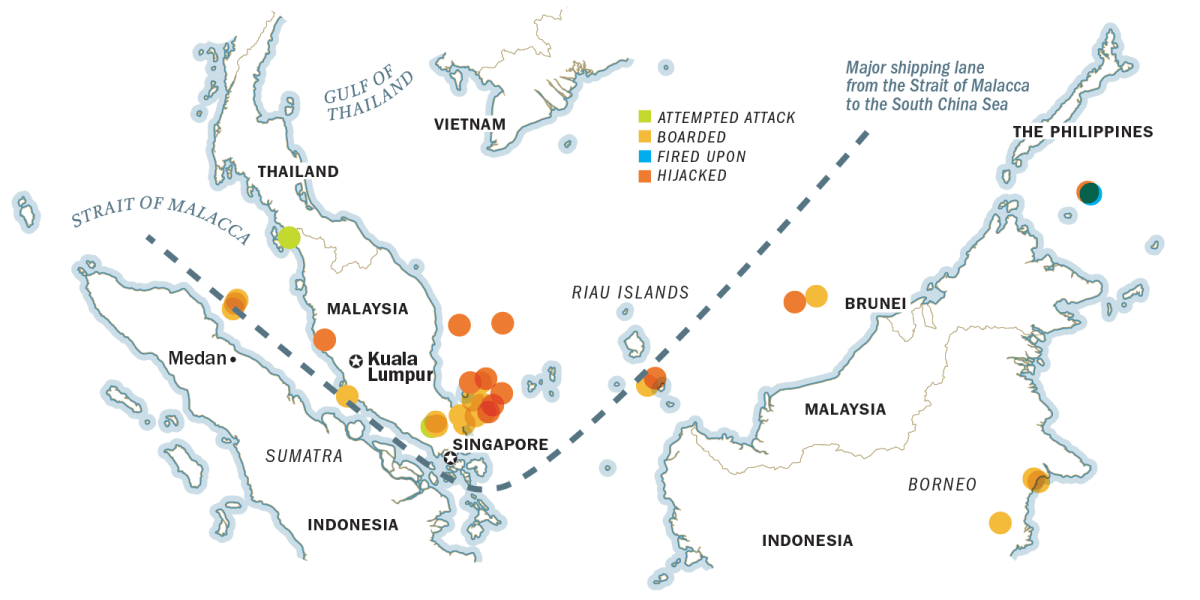

When the world thinks of piracy, it thinks of Somalia and red-eyed young brigands peering over the barrels of their Kalashnikovs. It thinks of the 2013 Hollywood movie Captain Phillips, which tells the story of the hijacking of the Maersk Alabama in 2009 and the capture of its American captain. But the waters of the West Indian Ocean are not the world’s most dangerous. Far from it. The most perilous seas, as the U.N. declared last month, are those of Southeast Asia — and for criminals they offer sumptuously rich pickings.

Stretching from the westernmost corner of Malaysia to the tip of Indonesia’s Bintan Island, the Malacca and Singapore straits serve as global shipping superhighways. Each year, more than 120,000 ships traverse these waterways, accounting for a third of the world’s marine commerce. Between 70% and 80% of all the oil imported by China and Japan transits the straits.

Southeast Asia was the location of 41% of the world’s pirate attacks between 1995 and 2013. The West Indian Ocean, which includes Somalia, accounted for just 28%, and the West African coast only 18%. During those years, 136 seafarers were killed in Southeast Asian waters as a result of piracy — that’s twice the number in the Horn of Africa, where Somalia lies, and more than those deaths and the fatalities suffered in West Africa combined.

According to a 2010 study by the One Earth Future Foundation, piracy drains between $7 billion and $12 billion dollars from the international economy each year. The Asian share of that represents buccaneering on a lavish scale, and it is becoming more ambitious. In recent months, well-armed and organized criminal groups have focused their efforts on the oil tankers that exit the narrow Malacca and Singapore straits and venture into the South China Sea. Here, the territory is vast, law enforcement’s resources are stretched, and the potential profits are immense.

While the majority of attacks are opportunistic — 80% of total incidents worldwide occur against anchored ships, with thieves looting equipment, crew members’ belongings and any cash found aboard — the attacks this spring have featured large-scale, sophisticated strikes on vessels at sea. These require military coordination and meticulous planning.

“This trend only started in the last three months, and we expect there will be more,” Nicholas Teo told TIME in June. A former commander in the Republic of Singapore Navy, Teo is now deputy director of the Information Sharing Center (ISC) of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia (or, as it’s mercifully abbreviated, ReCAAP). And yet, TIME’s investigation revealed evidence of this trend stretching back more than a year, with 14 oil-siphoning attacks since 2011. Of those 14 attacks, one specific company was targeted four times, a coincidence that experts suspect may be the result of a collusion between either the shipping company, or some members of the crew, and the alleged attackers.

“This trend only started in the last three months, and we expect there will be more,” Nicholas Teo told TIME in June. A former commander in the Republic of Singapore Navy, Teo is now deputy director of the Information Sharing Center (ISC) of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia (or, as it’s mercifully abbreviated, ReCAAP). And yet, TIME’s investigation revealed evidence of this trend stretching back more than a year, with 14 oil-siphoning attacks since 2011. Of those 14 attacks, one specific company was targeted four times, a coincidence that experts suspect may be the result of a collusion between either the shipping company, or some members of the crew, and the alleged attackers.

“We believe that there is some insider information,” Teo told TIME, citing the circumstances surrounding these specific attacks.

The Floating World

![]()

The Orapin 4 is one of 11 vessels registered to the Bangkok-based Thai International Tankers. In the past 12 months, the company has fallen victim to four separate pirate attacks: the first in August 2013, two more attacks within days of each other in October 2013, and the latest, against Orapin 4, in late May 2014. Given the number of vessels that traverse the region, the odds that these ships would all fall victim at random may seem remarkably low.

“At the ship level, it is really the captain that runs the operation,” says Karsten von Hoesslin, a special-projects manager for maritime security analysts Risk Intelligence. For the past decade, von Hoesslin has analyzed piracy from the Gulf of Guinea and Horn of Africa, to, more recently, the waters of Southeast Asia. Speaking hypothetically about oil thefts at sea, and not specifically about Orapin 4, he claims, “In order to move that much fuel that quickly, the captain and likely the chief engineer are involved.”

However, this was not the case with the Orapin 4.

“The captain and crew have been cleared,” Sudakorn Sengprasert, manager of Thai International Tankers, told TIME. After the incident, the company submitted the crew of Orapin 4 to an investigation by Thai police and a review by company lawyers.

Sengprasert said the attacks against the company were largely opportunistic, citing the vessels’ low freeboard (the distance that separates the surface of the water from the top deck) and the company’s high-value cargo, as precipitating causes. “Some other companies avoid shipping this cargo,” he said. However, Sengprasert conceded that particular details regarding the May 2014 attack — many collected by ReCAAP — had created cause for concern, prompting the company’s formal investigation.

For example, after the attack, in which the vessel’s communication and navigation equipment was damaged, the captain was able to reconnect the GPS equipment but decided to sail to the company’s home port, Sri Racha, instead of nearby Malaysia to report the attack to regional authorities. “He should have sailed to the nearest port,” said Sengprasert. He refused to clarify why the captain of another Thai International vessel, Danai 5, had also opted to sail back to home port, delaying the reporting of their October 2013 attack by crucial days.

Sengprasert said no charges were brought against Orapin 4’s captain or chief engineer. He told TIME that the captain had worked for the company for nearly two years on a series of two- to three-month contracts. However, the captain’s latest contract had expired, Sengprasert said, and he was “no longer employed” by Thai International Tankers. Sengprasert was unable to confirm whether the chief engineer was still working for the company. TIME also contacted the Shipowners’ Club, a marine liability insurer for the Thai firm, but were told that no one on staff was permitted to discuss current or ongoing cases.

Experts say that employment by short-term contract ensures the fluid movement and steady supply of personnel in the industry but can make it difficult to trace shipping companies, captains and their crews.

“In the past, you could be fairly sure, if you had a Russian vessel, that it would be owned by a Russian company, flying a Russian flag, had a Russian captain and a Russian crew,” says Peter Chalk, a maritime security researcher with the Rand Corp. think tank. Today, the system is much different. “It could be a Japanese-owned ship, sailing under a Panamanian flag, using an Indonesian captain with a Filipino crew.”

According to maritime experts, these varied arrangements create weak links between the myriad actors in the shipping industry. For instance, while a shipping company may be able to vet the captain of a ship, the captain will chose his crew, and that crew may have no contact with, much less loyalty to, the parent shipping company. These relationships often result in insufficient auditing of captains and sailors, and can increase the likelihood of theft and corruption.

In a separate incident in April, after pirates stole 2,500 metric tons of fuel from a small product tanker, Reuters cited unnamed regional security officials warning of “armed gangs prowling the Malacca Strait [who] may be part of a syndicate that can either have links to the crew on board the hijacking target or inside knowledge about the ship and cargo.”

Von Hoesslin witnessed similar collusion last fall. While conducting research in Pontianak, Indonesia, he heard of a chief engineer and captain selling information about an upcoming oil shipment, through a middleman, to a local criminal syndicate. With access to this information, the syndicate was able to commandeer the ship, steal its cargo and mix it with a second, legally obtained supply, before selling the mixed batch to an unwitting European buyer, von Hoesslin says.

“When you siphon liquids, a ship’s engineer has to know what they’re doing,” Michael Frodl, a maritime security expert whose company, C-LEVEL Maritime Risks, advises insurers, shipowners, governments and piracy-reporting organizations in the region. Because of the complexity of oil siphoning, the individuals involved in these attacks must have oil-industry experience and contacts through which to sell the pilfered oil. “They aren’t posting this on eBay or Craigslist,” Frodl adds.

Pirated oil is often mixed with legally obtained oil at sea in vessels referred to as mother ships, and it is difficult — if not impossible — to discern whether a given oil supply has been illegitimately obtained. The mixed oil, then, is resold to buyers whose owners, captains or crews may be ignorant of the fuel’s questionable origin. This fuel exchange, known as bunkering, may also take place at sea. According to its Port Authority, Singapore is the “largest and most important bunkering port in the world.”

Pirated oil is often mixed with legally obtained oil at sea in vessels referred to as mother ships, and it is difficult — if not impossible — to discern whether a given oil supply has been illegitimately obtained. The mixed oil, then, is resold to buyers whose owners, captains or crews may be ignorant of the fuel’s questionable origin. This fuel exchange, known as bunkering, may also take place at sea. According to its Port Authority, Singapore is the “largest and most important bunkering port in the world.”

“The modus operandi [in Southeast Asia] … is a general move away from pure robberies in transit and towards more elaborate hijackings for product theft targeting both product tankers and crude palm oil barges,” von Hoesslin wrote in Risk Intelligence’s 2013 year-end report. In another publication earlier this year, he said, “These hijackings are also under-reported … the true number of actual hijackings in South East Asia will never be known.”

To combat the attacks, organizations such as the Singapore navy’s Information Fusion Centre, ReCAAP’s ISC and the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), which monitors maritime security worldwide, have sought to improve information sharing, facilitate coordinated patrols and work with regional governments on more effective allocations of time and resources. While the response has been credited with shrinking the number of attacks in the region to a low of 47 in 2009, piracy has persisted, rising to 128 attacks in 2013, and 47 attacks already in 2014.

“If there is any bottom line in the fight against piracy, it is always resources,” says the ISC’s Teo, who works with ReCAAP’s 13 member countries. “The policeman has to be in the right place at the right time.”

Never Enough Men or Boats

![]()

The responsibility for putting policemen in the right place falls to people like Commander Benyamin Sapta, who commands 174 marine police officers based on Indonesia’s Batam Island. This year, 18 of the region’s 47 pirate attacks occurred in the waters surrounding Batam, which lies a mere 45-minute sail from Singapore’s main harbor.

A barrel-chested man with gelled and impeccably parted hair, Sapta affirms Jakarta’s commitment to fighting piracy but disagrees that attacks are on the rise. In January 2014, the Indonesian government announced a list of 10 hot spots of pirate activity. Ships began avoiding those areas and Sapta contends that, since then, small-scale pirate attacks have decreased. But earlier this year, an 11th hot spot, in the sea off Batam and Bintan islands, has been added, hinting at another part of the problem: the sheer size of territory to be covered.

Indonesia has 95,000 km of coastline. On any given patrol, officers in Sapta’s sector stop and search between two and five vessels — a fraction of the traffic. He adds that poor information sharing and the existence of maritime boundaries limit the effectiveness of his patrols. His officers, for example, cannot chase suspected pirates from international waters into the territorial waters of neighboring countries (known as the “right of hot pursuit”) unless prior permission is given. These restrictions often give suspects an opportunity to flee, he says.

In addition, the police department’s shallow-draft vessels are incapable of long-range patrolling and are often forced back to port when the weather turns rough. Sometimes, there aren’t even enough parts.

“That’s from America,” Tanjung, a young marine police officer, tells TIME, his arm raised toward a boat in dry dock covered in a white tarpaulin. The U.S. donated 19 patrol vessels to the Indonesian Marine Police in 2011, of which four were sent to Batam. Today, however, officers on the island have only three at their disposal. As for the fourth, “We cannot afford the parts to fix the engine,” Tanjung says.

Uncomfortable Partners

![]()

Seemingly petty regional politics are also hampering the fight against piracy. Neither Malaysia nor Indonesia is a member of ReCAAP. According to one source, who preferred not to be identified because of their ongoing work in the region, Malaysia does not want to see ReCAAP become a rival of the Kuala Lumpur–based IMB, and Indonesia wanted to host ReCAAP in Jakarta but lost the bid to Singapore.

“You are only as strong as your weakest link,” says the Rand Corp.’s Chalk. “When you don’t have intelligence coordination at the national level, it is very difficult to have it at the regional level.”

There is also mistrust of Singapore. “Malaysia and Indonesia may be willing to share, but they suspect ReCAAP and its Singaporean backers are unwilling to reciprocate information sharing,” says von Hoesslin. “Not because of the fear of corruption or leakages, but because Singapore is known to be an intelligence hoarder.”

For countries like Indonesia, where 40% of the world’s reported pirate attacks have occurred this year, information is, in any case, only part of the solution. Tackling graft must be another.

“Any policy addressing piracy would require a fight against not only national corruption but also local corruption,” says Eric Frécon, an assistant professor at the French Naval Academy and author of a study of Indonesian piracy, Chez les Pirates d’Indonésie.

Corruption in Indonesia puts it in 114th position out of 177 countries, according to Transparency International, and because of the decentralized nature of the Indonesian government, criminality has a strong regional character. There are 34 provincial offices in the sprawling archipelago, each with its own Regional Representative Council, overseeing, among other things, the management of natural resources and other economic assets — powers that can be exploited by local players. This July, Indonesia’s Corruption Court handed down its first-ever life sentence to Akil Mochtar, the former chief justice of Indonesia’s Constitutional Court. According to the New York Times, Mochtar benefited from the countries “regional oligarchies.” These centers of money and power have given rise to criminals of all stripes — but, most notably, pirates.

Frécon conducted a series of interviews with local sources on Batam between 2009 and 2012, and learned that the island’s pirate bosses (or “godfathers,” as he calls them) are enormously powerful. Not only can they ensure that their men receive better food and treatment behind bars, they can also secure them early release — typically just three months into a sentence of several years.

“What I’m worried about now in Southeast Asia is a very sophisticated criminal network that can target a product, oil, which can be moved overnight,” says Frodl. And it appears to be a network operating with impunity.

On Aug. 30, a motorized skiff pulled up along the portside of the Thai-registered oil tanker V.L.14, en route from Singapore to Thailand. It was just one of hundreds of skiffs amid hundreds of ships gleaming in the sun of the Singapore Strait, which is now so crowded with vessels that pirates can hide in plain sight. Six armed men scrambled aboard the V.L.14, where they ordered the crew to open all cargo valves and activate the cargo pump. Then, the pirates siphoned the ship’s oil into two waiting tankers and vanished over the horizon. It was a familiar script: after all, it was the 10th such attack in the region since April.

On Aug. 30, a motorized skiff pulled up along the portside of the Thai-registered oil tanker V.L.14, en route from Singapore to Thailand. It was just one of hundreds of skiffs amid hundreds of ships gleaming in the sun of the Singapore Strait, which is now so crowded with vessels that pirates can hide in plain sight. Six armed men scrambled aboard the V.L.14, where they ordered the crew to open all cargo valves and activate the cargo pump. Then, the pirates siphoned the ship’s oil into two waiting tankers and vanished over the horizon. It was a familiar script: after all, it was the 10th such attack in the region since April.

“There usually aren’t that many strikes in a short period of time,” maintains Noel Choong, a spokesperson for the IMB. “What people are concerned about is that if no one is trying to stop it, it is likely to continue.” For clarity, perhaps he should have said that people are trying to stop it, but piracy — rampant, industrial-scale organized piracy — is happening anyway.